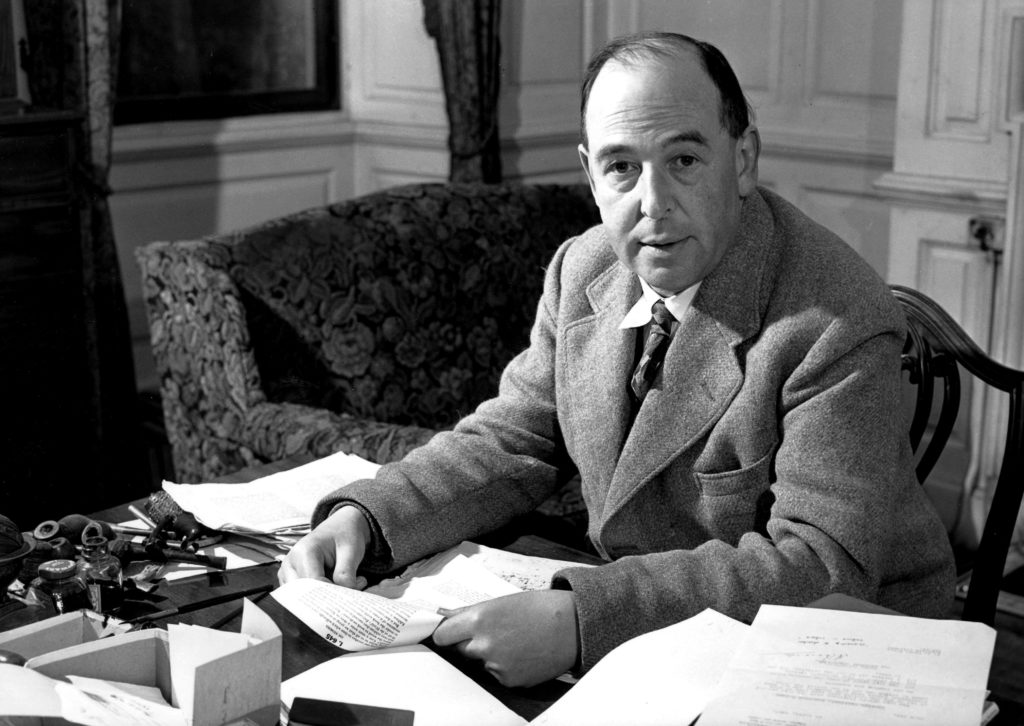

Oxford scholar C.S. Lewis is known throughout most of the world for The Cronicles of Narnia. To a Danish audience at least, it is perhaps less well-known that Lewis ranks among the most acute christian thinkers of the twentieth century and author of one the finest memoirs of loss in western literature: A Grief Observed.

In his academic work, Lewis devoted much of his attention to suffering and the problem of pain, which he argued is essential to the development of man:

I suggest to you that it is because God loves us that he gives us the gift of suffering. Pain is God’s megaphone to rouse a deaf world. You see, we are like blocks of stone out of which the Sculptor carves the forms of men. The blows of his chisel, which hurt us so much are what make us perfect.

C.S. Lewis, the problem of pain (1940)

You might also like: Nonfiction Guide: Gode tekster dine elever ikke kender

Surprised by Joy

However succinct, Lewis’ thoughts on the necessity of suffering took a turn when confronted with reality. In April 1956, Lewis, a confirmed bachelor, married Joy Davidman, an American Poet with two small children. After four intensely happy years, Davidman died of cancer and Lewis found himself alone again and inconsolable.

The story of the shortlived love between the sedate academic and the spirited American poet is told with quiet beauty in Shadowlands (1993) starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. The film builds on William Nicholson’s stageplay of the same name which itself takes its inspiration from Lewis’ diary of loss published in 1961.

A kind of parallel to his autobiography Surprised by Joy (1955), A Grief Observed freely confesses Lewis’ pain, rage and struggle to sustain his faith. But in dealing with his acute sense of loss in writing he manages to find a way back to life.

The ambiguity of the title reveals much about the situation Lewis finds himself in. The verb “observe” means to watch something carefully in order to learn more about it. And Lewis – the scholar – certainly takes a hard look at his emotional suffering and commits his observations to paper. To observe, however, may also be to follow rules or obey laws. In public, we often pay our respects to someone by observing a minute of silence.

A Grief Observed

This double-bind is really at the heart of the matter. Lewis grieves inside and out. As a philosopher, he analyzes and reflects intelligently on his pain, but as a bereaved husband he is inescapably tied down by the same pain. The loss of Joy is simultaneously intellectualy distancing and desperately immediate. Just read Lewis opening reflections in A Grief Observed:

No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.

At other times it feels like being mildly drunk, or concussed. There is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me. I find it hard to take in what anyone says. Or perhaps, hard to want to take it in. It is so uninteresting. Yet I want the others to be about me. I dread the moments when the house is empty. If only they would talk to one another and not to me.

There are moments, most unexpectedly, when something inside me tries to assure me that I don’t really mind so much, not so very much, after all. Love is not the whole of a man’s life. I was happy before I ever met H. I’ve plenty of what are called ‘resources’. People get over these things. Come, I shan’t do so badly. One is ashamed to listen to this voice but it seems for a little to be making out a good case. Then comes a sudden jab of red-hot memory and all this ‘commonsense’ vanishes like an ant in the mouth of a furnace.

On the rebound one passes into tears and pathos. Maudlin tears. I almost prefer the moments of agony. These are at least clean and honest. But the bath of self-pity, the wallow, the loathsome sticky-sweet pleasure of indulging it – that disgusts me. And even while I’m doing it I know it leads me to misrepresent H herself. Give that mood its head and in a few minutes I shall have substituted the real woman for a doll to be blobbered over. Thank God the memory of her is still too strong (will it always be too strong?) to let me get away with it.

C.s. lewis, a grief observed (1961)

Forbidding Mourning

The thoughts and reflections of A Grief Observed may in some ways be seen as the antithesis to those expressed by poet and philosopher John Donne in his playfully beautiful love poem A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning. In Donne’s poem, the poet is about to leave his lover and go on a journey. In doing so he tries to soften the pain of separation by comparing their love to a compass. Just like the legs of a compass, the poet argues, the lovers will always be connected and thus their love will only expand as the distance between them grows.

As virtuous men pass mildly away,

And whisper to their souls to go,

Whilst some of their sad friends do say

The breath goes now, and some say, No:So let us melt, and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move;

‘Twere profanation of our joys

To tell the laity our love.Moving of th’ earth brings harms and fears,

Men reckon what it did, and meant;

But trepidation of the spheres,

Though greater far, is innocent.Dull sublunary lovers’ love

(Whose soul is sense) cannot admit

Absence, because it doth remove

Those things which elemented it.But we by a love so much refined,

That our selves know not what it is,

Inter-assured of the mind,

Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss.Our two souls therefore, which are one,

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to airy thinness beat.If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two;

Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if the other do.And though it in the center sit,

Yet when the other far doth roam,

It leans and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

john donne, a valediction: forbidding mourning (1612)

Like th’ other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun.

This is of course all well and good when the separation is the temporary result of travel and not of death. In his diary, Lewis makes use of similar imagery of circles and spheres to describe his desperate want in the knowledge that death is finite and the separation is forever:

Suppose that the earthly lives she and I shared for a few years are in reality only the basis for, or prelude to, or earthly appearance of, two unimaginable, super-cosmic, eternal somethings. Those somethings could be pictured as spheres or globes. Where the plane of Nature cuts through them – that is, in earthly life – they appear as two circles (circles are slices of spheres). Two circles that touched. But those two circles, above all the point at which they touched, are the very thing I am mourning for, homesick for, famished for.

You tell me ‘she goes on’. But my heart and body are crying out, come back, come back. Be a circle, touching my circle on the plane of Nature. But I know this is impossible. I know that the thing I want is exactly the thing I can never get. The old life, the jokes, the drinks, the arguments, the lovemaking, the tiny, heartbreaking commonplace. On any view whatever, to say ‘H is dead’, is to say ‘All that is gone’. It is part of the past. And the past is the past and that is what time means, and time itself is one more name for death, and Heaven itself is a state where ‘the former things have passed away.’

C.S. lewis, a grief observed (1961)