Velkommen til the Nonfiction Guide. Det er altid en tidskrævende proces at finde gode tekster til undervisning. Eleverne har adgang til bjerge af study guides og hjælpemidler til at skrive om tidligere eksamenstekster, så hvordan får vi overblik over deres niveau – og vigtigst af alt: hvordan lærer de at tænke selv? Samtidig er det at lave nye opgaver til hver aflevering et Sisyfos-arbejde ingen får tid eller betaling for. Men det kan være rart nok at stikke eleverne en helt ukendt tekst i ny og næ.

I denne artikel har jeg samlet 9 bud på gode nonfiction tekster, der rækker ud over den gængse tale eller nyhedsartikel. Forslagene tager udgangspunkt i artiklen “Ten Best Essay Collections of the Decade” på Literary Hub, The Electric Typewriter – et ekstraordinært ressourcecenter for all things nonfiction – og Maria Popovas inspirationsguldgrube Brain Pickings.

Jeg har valgt essays til et bredt udvalg af emner f.eks.:

- Violence (school shootings)

- Aspects of Life and Death

- Black America

- Gender

- The Sixties

- Growing Up

- Racial Frontiers

- Happiness

Nogle af teksterne er ret lange og jeg har ikke villet forkorte dem, men der skulle være gode muligheder for at bruge uddrag til skriftlige opgaver.

Joy by Zadie Smith

It might be useful to distinguish between pleasure and joy. But maybe everybody does this very easily, all the time, and only I am confused. A lot of people seem to feel that joy is only the most intense version of pleasure, arrived at by the same road—you simply have to go a little further down the track. That has not been my experience. And if you asked me if I wanted more joyful experiences in my life, I wouldn’t be at all sure I did, exactly because it proves such a difficult emotion to manage. It’s not at all obvious to me how we should make an accommodation between joy and the rest of our everyday lives.

ZAdie smith, the New york review of books (2013)

Læs også: Nonfiction i engelsk: Lær dine elever at skrive med sanserne

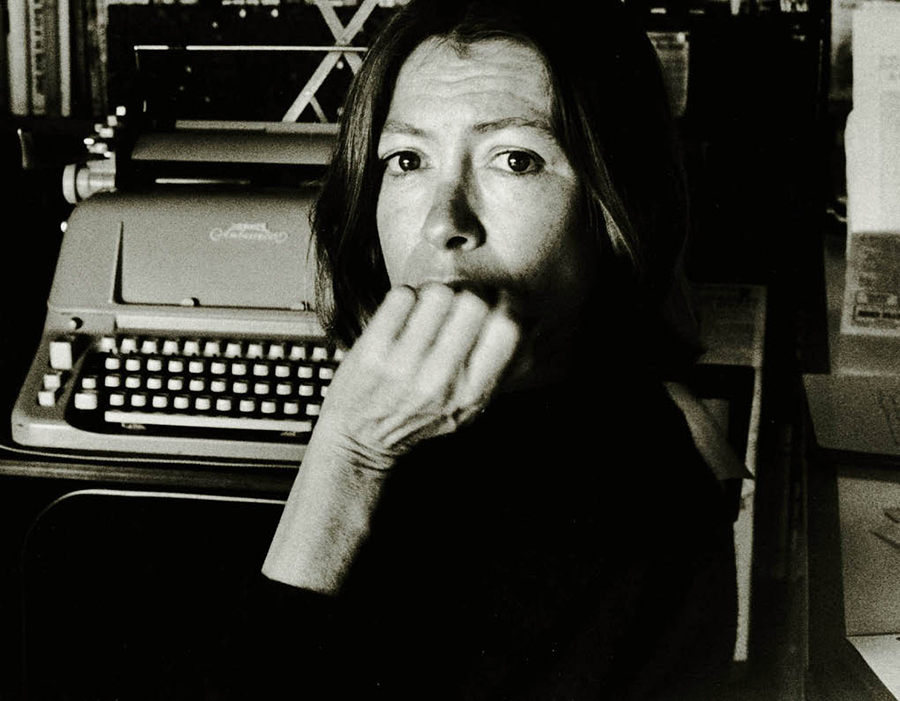

Goodbye to All That by Joan Didion

How many miles to Babylon?

Joan didion,slouching towards bethlehem (1967)

Three score miles and and ten—

Can I get there by candlelight?

Yes, and back again—

If your feet are nimble and light

You can get there by candlelight.

It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends. I can remember now, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, when New York began for me, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment it ended, can never cut through the ambiguities and second starts and broken resolves to the exact place on the page where the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was. When I first saw New York I was twenty, and it was summertime, and I got off a DC-7 at the old Idlewild temporary terminal in a new dress which had seemed very smart in Sacramento but seemed less smart already, even in the old Idlewild temporary terminal, and the warm air smelled of mildew and some instinct, programmed by all the movies I had ever seen and all the songs I had ever read about New York, informed me that it would never be quite the same again.

Feet in Smoke by John Jeremiah Sullivan

On the morning of April 21, 1995, my elder brother, Worth (short for Ellsworth), put his mouth to a microphone in a garage in Lexington, Kentucky, and in the strict sense of having been “shocked to death,” was electrocuted. He and his band, the Moviegoers, had stopped for a day to rehearse on their way from Chicago to a concert in Tennessee, where I was in school. Just a couple of days earlier, he had called to ask if there were any songs I wanted to hear at the show. I asked for something new, a song he’d written and played for me the last time I’d seen him, on Christmas Day. Our holidays always end the same way, with the two of us up late drinking and trying out our new “tunes” on each other. There’s something biologically satisfying about harmonizing with a sibling. We’ve gotten to where we communicate through music, using guitars the way fathers and sons use baseball, as a kind of emotional code.

John Jeremiah sullivan, pulphead (2011)

Thresholds of Violence by Malcolm Gladwell

On the evening of April 29th last year, in the southern Minnesota town of Waseca, a woman was doing the dishes when she looked out her kitchen window and saw a young man walking through her back yard. He was wearing a backpack and carrying a fast-food bag and was headed in the direction of the MiniMax Storage facility next to her house. Something about him didn’t seem right. Why was he going through her yard instead of using the sidewalk? He walked through puddles, not around them. He fiddled with the lock of Unit 129 as if he were trying to break in. She called the police. A group of three officers arrived and rolled up the unit’s door. The young man was standing in the center. He was slight of build, with short-cropped brown hair and pale skin. Scattered around his feet was an assortment of boxes and containers: motor oil, roof cement, several Styrofoam coolers, a can of ammunition, a camouflage bag, and cardboard boxes labelled “red iron oxide,” filled with a red powder. His name was John LaDue. He was seventeen years old.

Malcolm gladwell, the new yorker (2015)

Læs også: Narrative Journalism from the Pulitzer Files

What is Water? by David Foster Wallace

(If anybody feels like perspiring [cough], I’d advise you to go ahead, because I’m sure going to. In fact I’m gonna [mumbles while pulling up his gown and taking out a handkerchief from his pocket].) Greetings [“parents”?] and congratulations to Kenyon’s graduating class of 2005. There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

This is a standard requirement of US commencement speeches, the deployment of didactic little parable-ish stories. The story [“thing”] turns out to be one of the better, less bullshitty conventions of the genre, but if you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise, older fish explaining what water is to you younger fish, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish. The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude, but the fact is that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance, or so I wish to suggest to you on this dry and lovely morning.

David foster wallace, kenyon college commencement address (2005)

A Letter to my Nephew by James Baldwin

Dear James:

James Baldwin, The progressive (1962)

I have begun this letter five times and torn it up five times. I keep seeing your face, which is also the face of your father and my brother.I have known both of you all your lives and have carried your daddy in my arms and on my shoulders, kissed him and spanked him and watched him learn to walk. I don’t know if you have known anybody from that far back, if you have loved anybody that long, first as an infant, then as a child, then as a man. You gain a strange perspective on time and human pain and effort.

Difficult Girl by Lena Dunham

I am eight, and I am afraid of everything. The list of things that keep me up at night includes but is not limited to: appendicitis, typhoid, leprosy, unclean meat, foods I haven’t seen emerge from their packaging, foods my mother hasn’t tasted first so that if we die we die together, homeless people, headaches, rape, kidnapping, milk, the subway, sleep.

Lena dunham, the new yorker (2014)

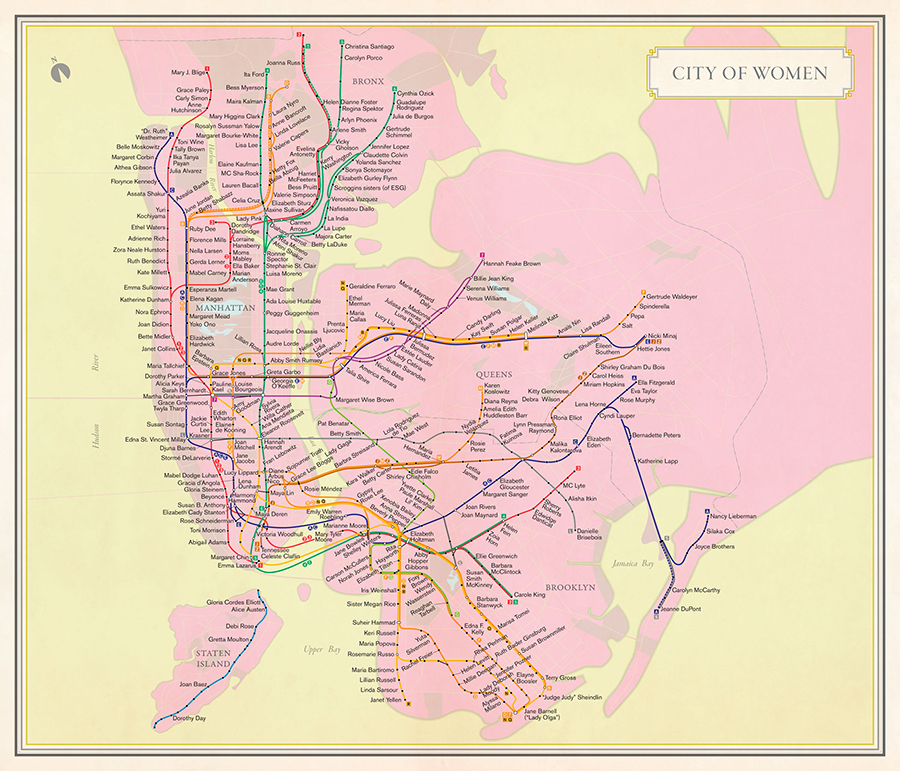

City of Women by Rebecca Solnit

It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” is a song James Brown recorded in a New York City studio in 1966, and, whether you like it or not, you can make the case that he’s right. Walking down the city streets, young women get harassed in ways that tell them that this is not their world, their city, their street; that their freedom of movement and association is liable to be undermined at any time; and that a lot of strangers expect obedience and attention from them. “Smile,” a man orders you, and that’s a concise way to say that he owns you; he’s the boss; you do as you’re told; your face is there to serve his life, not express your own. He’s someone; you’re no one.

REbecca solnit, Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas (2016)

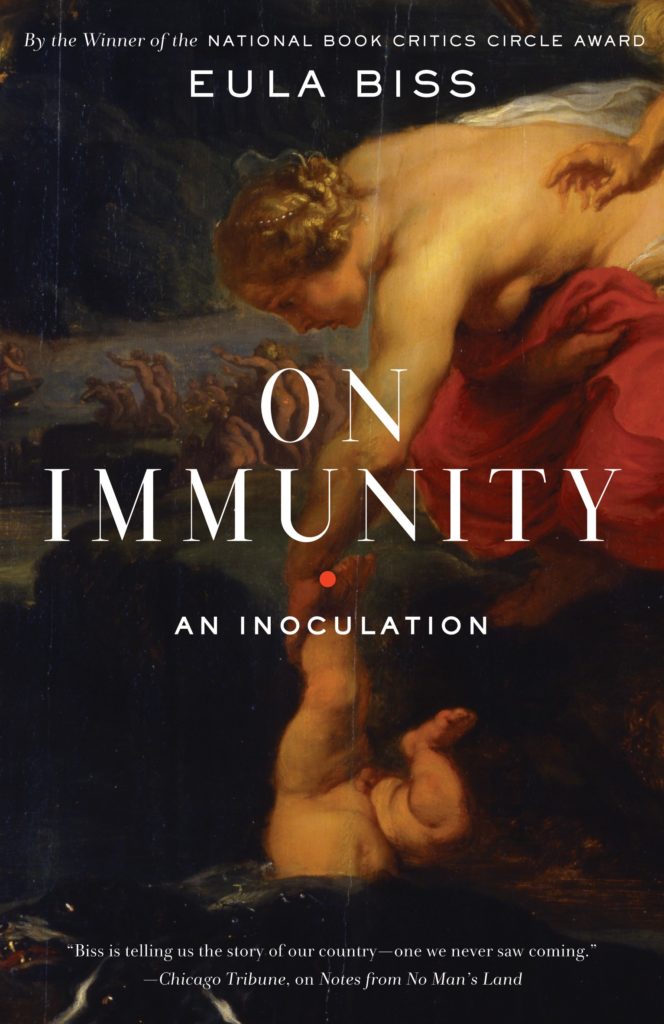

No Man’s Land by Eula Biss

“What is it about water that always affects a person?” Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote in her 1894 diary. “I never see a great river or lake but I think how I would like to see a world made and watch it through all its changes.”

Forty years later, she would reflect that she had “seen the whole frontier, the woods, the Indian country of the great plains, the frontier towns, the building of the railroads in wild unsettled country, homesteading and farmers coming in to take possession.” She realized, she said, that she “had seen and lived it all….”

It was a world made and unmade. And it was not without some ambivalence, not without some sense of loss, that the writer watched the Indians, as many as she could see in either direction, ride out of the Kansas of her imagination. Her fictional self, the Laura of Little House on the Prairie, sobbed as they left. Like my sister, like my cousin, like so many other girls, I was captivated, in my childhood, by that Laura. I was given a bonnet, and I wore it earnestly for quite some time. But when I return to Little House on the Prairie now as an adult, I find that it is not the book I thought it was. It is not the gauzy frontier fantasy I made of it as a child. It is not a naïve celebration of the American pioneer. It is the document of a woman interrogating her legacy. It is, as the scholar Ann Romines has called it, “one of our most disturbing and ambitious narratives about failures and experiments of acculturation in the American West.”

Eula biss, notes from no man’s land: american Essays (2009)